2 Idealised

2.1 Introducing Ideal Theory

Game theorists, like philosophical decision theorists, are doing ideal theory. To see that they are doing ideal theory, compare what they say about two problems: Salesman and Basketball. The first is a version of what Julia Robinson dubbed the ‘travelling salesman’ problem.1

1 The dubbing is in Robinson (1949). For a thorough history of the problem, see Schrijver (2005). For an accessible history of the problem, which includes these references, see the wikipedia page on ‘Traveling Salesman Problem’.

Salesman

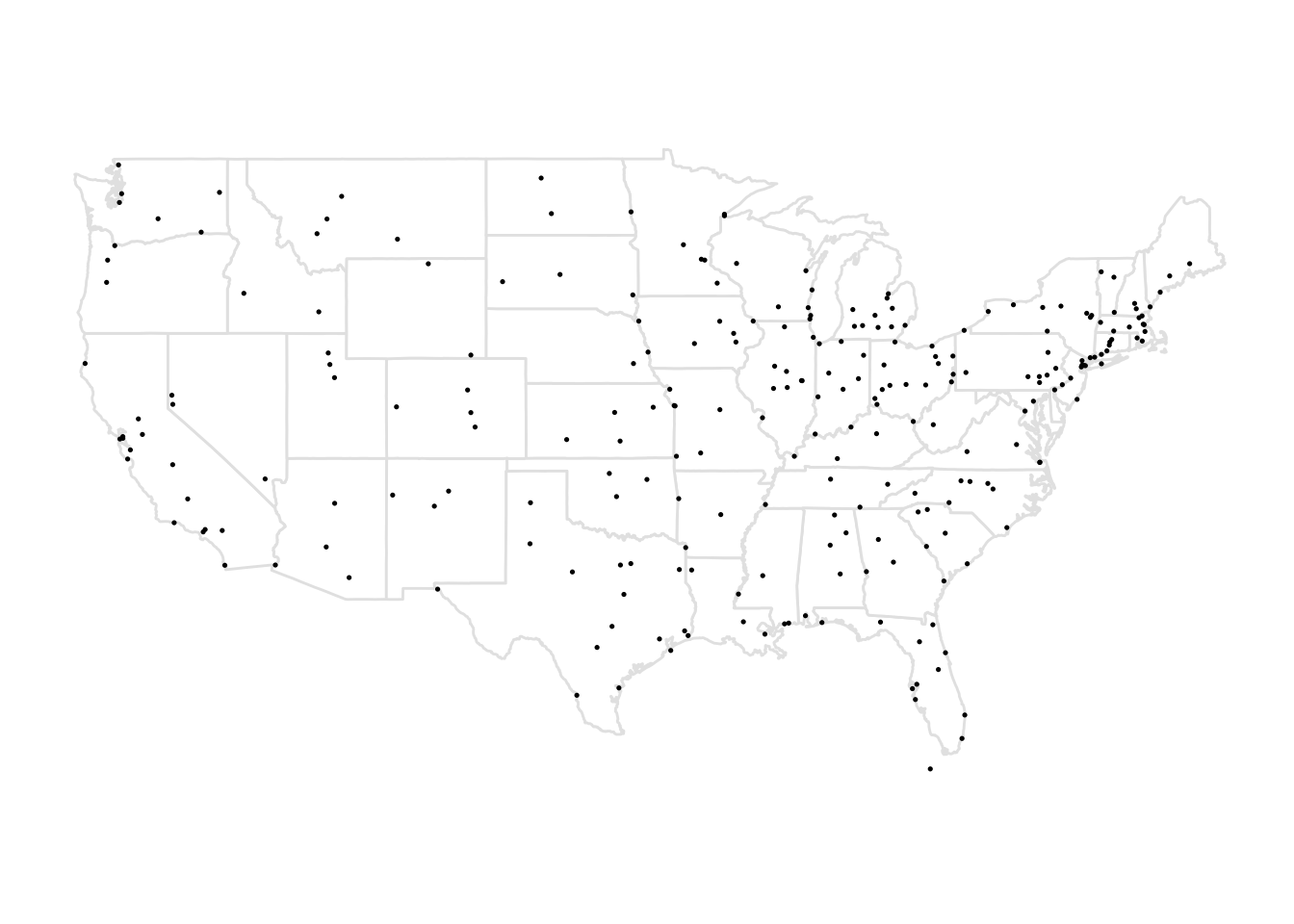

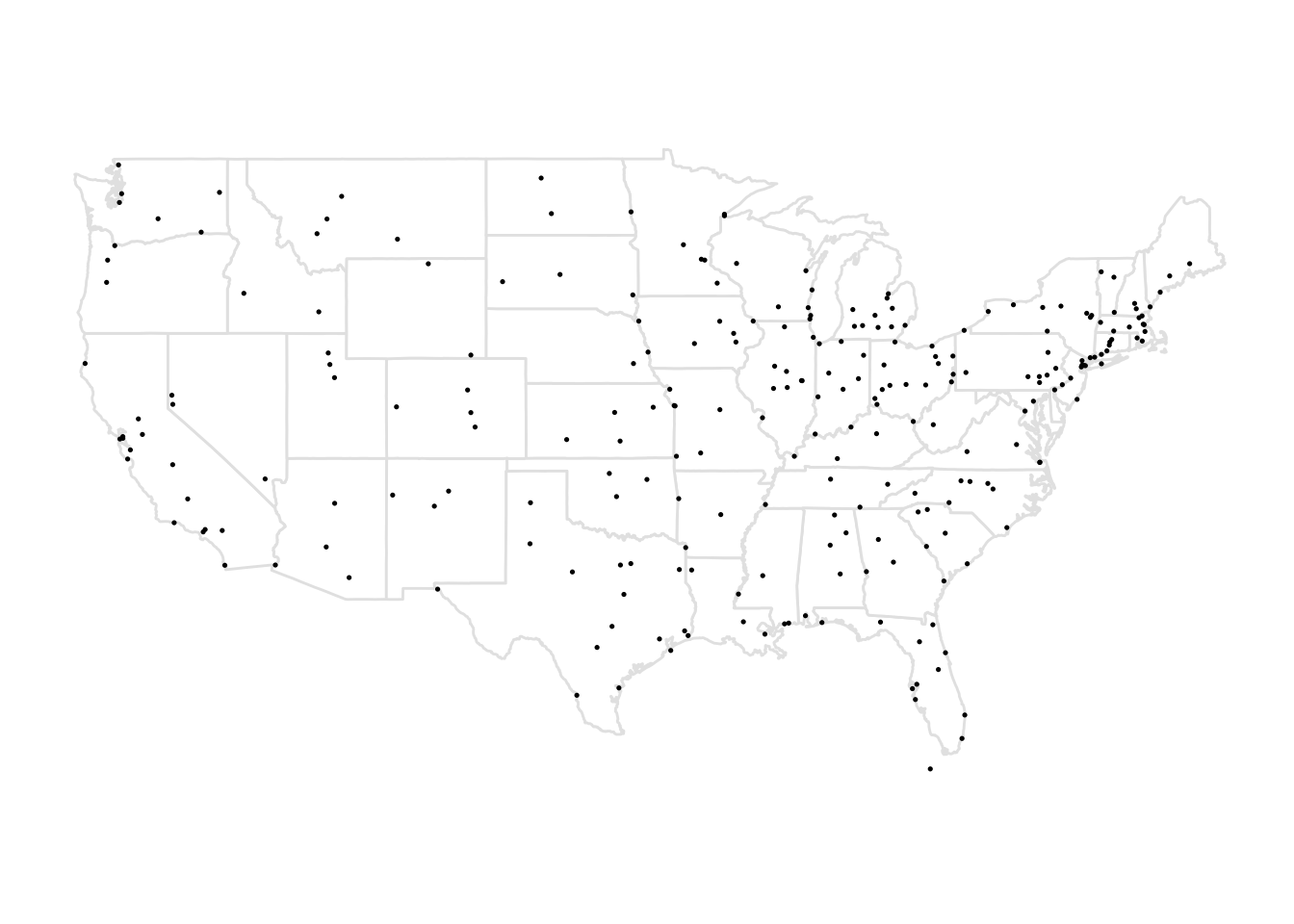

Chooser is given the straight line distance between each pair of cities from the 257 represented on the map in Figure 2.1. Using this information, Chooser has to find as short a path as possible that goes through all 257 cities and returns to the first one. The longer a path Chooser selects, the worse things will be for Chooser.

Since there are 256! possible paths, and 256! ≈ 10727, Chooser has a few options here.2 Game theorists, and philosophical decision theorists, start with the assumption that the people in their models can solve these problems in zero time and at zero cost. Or, at the very least, that the people can emulate someone who solves these problems in zero time and at zero cost. That’s not even approximately true for any actual person without technological assistance. Even with knowledge of the problem and a good computer, there are not that many actual people who you could properly model as being able to solve it in zero time and at zero cost.

2 The 257 cities are the cities in the lower 48 states from the 312 cities in North America that John Burkardt mapped in his dataset Cities, available at people.sc.fsu.edu/~jburkardt/datasets/cities/cities.html.

3 I’m borrowing the term ‘non-ideal’ from work in political philosophy. See Valentini (2012) for a good survey of some relevant work, and Mills (2005) for an important critique of the centrality of ideal theory in political philosophy. Critics of ideal theory, such as Mills, and Sen (2006), argue that we shouldn’t base non-ideal theory on ideal theory. I’m going to agree, but my focus is primarily in the other direction. I’m going to argue that it isn’t a constraint on ideal theory that it is useful in constructing a non-ideal theory.

The question of how to think about people who do have to spend time and resources to solve a problem like this is an interesting one. We might call that problem one in non-ideal decision theory.3 I won’t say much about non-ideal decision theory in the body of this book, though I’ll come back to it in Appendix B. What I mostly want to do now is use Salesman to say something about what the difference between ideal and non-ideal theory is. And that difference is brought up vividly by the following problem.

Basketball

Chooser is at a casino, and a basketball game is about to start. Chooser knows that basketball games don’t have draws or ties; one side will win. And Chooser knows the teams are equally balanced; each team is 50% likely to win. Chooser has three options. They can bet on the Home team to win, bet on the Away team to win, or Pass, and not bet. If they bet, they win $100 if the team they bet on wins, and lose $110 if that team loses. If they Pass, they neither gain nor lose anything.

Ideal decision theory says that in Basketball, Chooser should Pass. That’s not the optimal outcome for Chooser. The optimal outcome is that they bet on the winning team. But since they don’t know who that is, and either bet will, on average, lose them money, they should Pass rather than bet on Home or Away. We could have a theory that just evaluated the possible outcomes in any decision. I’ll call this Outcome Evaluation Theory. Contrast this with two other theories. Game theory says that the ideal agent chooses the shortest route, whatever it is, in Salesman and does not bet in Basketball. If an ordinary reasonable person was advising a friend facing these two problems, they would give the same advice as the game theorist about Basketball, but in Salesman they would not simply say Choose the shortest path!, since that’s useless advice. Rather they would suggest something about how to solve the problem, possibly by looking up strategies.

So we have three theories on the table: Outcome Evaluation Theory; the game theory approach, which I’ll call Ideal Decision Theory; and the ordinary reasonable person approach, which I’ll call Non-Ideal Decision Theory. We can distinguish these three theories by what they say to do in two examples introduced so far: Salesman and Basketball.

| Theory | Salesman | Basketball |

|---|---|---|

| Outcome Evaluation | Shortest route | Bet on winner |

| Ideal Decision | Shortest route | Pass |

| Non-Ideal Decision | Study optimization | Pass |

Game theory agrees with the middle row. GDT, the theory I’m developing in this book, does so too. And so do almost all decision theorists working in philosophy.4 So in trying to convince philosophers to adopt GDT, I’m not asking them to change their view on this point. But still, this is odd. What is the benefit of a theory of decision that does not produce the best outcomes, and does not produce useful, reasonable advice?

4 The exceptions are people working in ‘descriptive decision theory’ (Chandler, 2017). But that’s normally not taken to be a normative theory; it isn’t about what people should do in problems like Salesman, but what they actually do.

5 This claim isn’t obvious. Why should being ideal require computational perfection, but not informational perfection? I’ll have more to say about this in Section 2.3.

6 This is a special case of Lipsey and Lancaster’s Theory of the Second Best (Lipsey & Lancaster, 1956). If you don’t have control over every parameter, setting the parameters you do control to the ideal values is generally inadvisable.

We could say that if Chooser were ideal, they would agree with Ideal Decision Theory.5 But why we should care about what would have if Chooser were ideal, since Chooser is not in fact ideal? One might think that knowing what the ideal is gives Chooser something to aim for. Even if Chooser is not ideal, they can try to be closer to the ideal. The problem is that trying to be more like the ideal will make things worse. The ideal agent will announce the best answer they have after spending no time calculating the solution to Salesman, and resembling the ideal agent in that respect will make Chooser worse.6 And there is a separate problem. Why say it is ideal to make a choice in Basketball that Chooser knows will lead to a sub-optimal outcome? We can make progress on both these problems, what it means to say something is ideal, and why we should care about the ideal, but stepping back and asking what we even mean by ‘ideal’, and ‘idealisation’.

In philosophy, it turns out we have two very different uses of the term ‘idealisation’. One is the kind of idealisation we see in, for example, Ideal Observer theories in ethics. The other is the kind of idealisation we see in, for example, Ideal Gas models in chemistry. It’s important to not confuse the two. Think about the volumeless, infinitely dense, molecules in an Ideal Gas model. To say that this is an idealised model is not to say that having volume, taking up space, is an imperfection. The point is not to tell molecules what the perfect size is. (“The only good molecule is a volumeless molecule.”) Nor is it to tell them that they should approximate the ideal. (“Smaller the better, fellas.”) It’s to say that for some predictive and explanatory purposes, molecules behave no differently to how they would behave if they took up no space.7

7 I’m drawing here on work on the nature of idealisations by Michael Strevens (2008) and by Kevin Davey (2011).

The best way to understand game theorists, and most philosophical decision theorists, is that they are using idealisations in this latter sense. The ideal choosers of decision theory are not like the Ideal Observers in ethics, but like the Ideal Gases. The point of the theory is to say how things go in a simplified version of the case, and then argue that this is useful for predictive and explanatory purposes because, at least some of the time, the simplifications don’t make a difference.

2.2 Uses of Ideal Theory

Still, this approach raises two pressing questions. One is why we should be interested in a model that is so idealised. The other is why we don’t idealise even further, idealising away from informational limitations as well as computational ones.8

8 John Conlisk (1996) stresses that explaining the asymmetry here is a big part of the challenge. That paper had a big influence in how I’m thinking about the problem, and several of the citations below are from it.

All social sciences use idealised models of some kind or other. The fact that real humans can’t solve problems like Salesman, but the modelled humans can, isn’t in itself a problem. Modelled humans are always different in some respects to real humans. It is only a problem if the differences matter. For example, if you are trying to model when humans fail at maximisation problems, don’t use a model that idealises away from computational limitations.

The real challenge is that some idealisations are useless. If all we end up saying is that when it’s more likely to rain, more people take umbrellas, we don’t need books full of math to say that. Here’s how Keynes puts the complaint, in a closely related context.

But this long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead. Economists set themselves too easy, too useless a task if in tempestuous seasons they can only tell us that when the storm is long past the ocean will be flat again. (Keynes, 1923: 80, emphasis in original)

Don’t focus on the temporal connotations of Keynes’s terminology of ‘long run’. What’s characteristic of his long run is not that it takes place in the distant future. What is characteristic of it instead is that it takes place in a world where some sources of interference are absent. It’s a world where we sail but there are no storms. It’s a study where we abstract away from storms and other unfortunate complications. And that’s what’s characteristic of Ideal Decision Theory. We know that people cannot easily solve hard arithmetic problems, but we abstract away from that fact. Does this leave the resulting theory “easy and useless”?

To see that it’s not “easy”, it simply suffices to take a casual glance at any economics journal. But what about Keynes’s suggestion that it is “useless”? It turns out there are some surprising results that we need the details of something like GDT to generate. One nice case of this is the discussion of Gulf of Mexico oil leases in Wilson (1967).9 Another example of this working is George Akerlof’s discussion of the used car market Akerlof (1970). In the twentieth century, it was common for lightly used cars to sell at a massive discount to new cars. There was no good explanation for this, and it was often put down to a brute preference for new cars. What Akerlof showed was that a model where (a) new cars varied substantially in quality, and (b) in the used car market, buyers had less information about the car than sellers, you could get a discount similar to what you saw in real life even if the buyers had no special preference for new cars. Rather, buyers had a preference for good cars, and took the fact that a car was for resale within months of being first bought to be evidence that it was badly made. It was important for Akerlof’s explanatory purposes that he could show that people were being rational, and this required that he have a decision theory that they followed. In fact what he used was something like GDT. We now have excellent evidence that something like his model was correct. As the variation in quality of new cars has declined, and the information available to buyers of used cars has risen, the used car discount has just about vanished. (In fact it went negative during the COVID-19 pandemic, for reasons I don’t at all understand.)

9 I learned about this paper from the excellent discussion of the case in Sutton (2000).

10 Bonanno (2018: 216) makes a somewhat similar point with the example of the drowning dog.

Here’s an even simpler surprising prediction that you need something like GDT to get, and which is relevant to some debates in philosophical decision theory.10 Imagine Row and Column are playing rock-paper-scissors. A bystander, C, says that he really likes seeing rock beat scissors, so he will pay whoever wins by playing rock $1. Assuming that Row and Column have no ability to collude, the effect of this will to add c to the value of playing Rock against Scissors, where c is the value of the dollar compared to the value of winning the game. This changes the game they are playing from Table 2.2 (a) to Table 2.2 (b).

| Rock | Paper | Scissors | |

| Rock | 0,0 | -1,1 | 1,-1 |

| Paper | 1,-1 | 0,0 | -1,1 |

| Scissors | -1,1 | 1,-1 | 0,0 |

| Rock | Paper | Scissors | |

| Rock | 0,0 | -1,1 | 1+c,-1 |

| Paper | 1,-1 | 0,0 | -1,1 |

| Scissors | -1,1+c | 1,-1 | 0,0 |

The surprising prediction is that this will decrease the frequency with which the bystander gets their way. The incentive will not make either party play rock more often, they will still play it one third of the time, but the frequency of scissors will decrease, so the rock smash outcome will be less frequent. Moreover, the bigger the incentive, the larger this increase will be11. Simple rules like “When behaviour is rewarded, it happens more often” don’t always work in strategic settings, and it takes some care to tell when they do work.

11 The proof is in Appendix C.

The point of decision theory is not to advise people on what to do in Rock-Paper-Scissors, or in Salesman. In each case, it would give bad advice. Really you should try to read your opponent’s body shape for clues in Rock-Paper-Scissors, and find some good software in Salesman. You won’t find either of those bits of advice in a game theory, or decision theory, text. Rather, the point is be part of explanations like why there was such a large discount on used cars in the 20th century, and why the bystander’s gambit won’t work in my modified version of Rock-Paper-Scissors. David Lewis gives a similar account of the purpose of decision theory in a letter to Hugh Mellor. The context of the letter, like the context of this section, is a discussion of why idealisations are useful in decision theory. Lewis writes,

We’re describing (one aspect of) what an ideally rational agent would do, and remarking that somehow we manage to approximate this, and perhaps – I’d play this down – advising people to approximate it a bit better if they can. (Lewis, 2020: 432)

2.3 Why This Idealisation

Still, there are a lot of ways to idealise away from the details of individual humans. Why do we delete the differences from rationality, and not the differences from full-informedness, or the differences from something that lacks normative significance? One simple answer is that people have used this idealisation and it has (to some extent) worked. But there is a little more to say.

Take some generalisation about human choosers that isn’t particularly rational, is true in most but not all cases, and which it would simplify our description of various cases to say it holds in all cases. Why don’t we use the idealisation that says it does in fact hold in all cases? The answer here depends a bit on the ‘we’. Some generalisations about less than ideally rational behavior are useful in empirical studies of consumer choice.12 But there is a reason that philosophers and more theoretical economists have focussed on rational idealisations. The thought is that a lot of deviations from rationality are short-cuts that are sensible to use when the stakes are low. But in high-stakes situations, humans will more closely approximate ideally rational agents. (This might be coupled with the suggestion that over time they will do this better, simply because the ones who more closely approximate the rational choice will increase their market share.) And getting correct predictions and explanations in high-stakes cases might be particularly important in understanding society and the economy. So while non-rational idealisations might be crucially important in understanding store design (e.g., why supermarkets have produce at the entrance), rational idealisations are needed for understanding the nature of stock markets and business investment.

12 See Barta, Gurrea, & Flavián (2023) for a relatively recent example, picked more or less at random.

That reasoning looks like it might over-generate. In high-stakes cases, people are not only more careful with their decision making process, they are more careful about acquiring information before they decide. If our focus is high-stakes decision making, and I think it has to be to motivate rational idealisations, why don’t we also abstract away from informational limitations of the deciders? After all, the decider will try to remove those limitations before deciding in these high-stakes cases. The answer is that in some cases, and these are the cases that decision theory is most useful in explaining, there are in principle reasons why the decider can’t do anything about certain informational limitations. The information might be a fact about the result of a chance-like process that is unknowable either in principle, or in any practical way. Or there might be someone else who has just as much incentive to keep the information hidden as the decider has to seek it out. The latter is what happens when someone is selling a lemon, for example. I don’t have anything like a proof of this, but I suspect that most uses of game theory or decision theory to explain real-world phenomena will fall into one or other of these categories: there are relevant facts that the decider can’t know, either because they have to decide before decisive evidence is revealed, or because someone just as well resourced as them is determined to prevent them getting the information.

2.4 Two Bonus Uses

There are two other advantages to using the particular idealisation that game theorists and decision theorists have settled on, i.e., idealise away from computational but not informational limitations. The first can be seen from this famous quote from Frank Knight, an early proponent of the view of idealisations in decision theory that I’m endorsing here.

It is evident that the rational thing to do is to be irrational, where deliberation and estimation cost more than they are worth. That this is very often true, and that men still oftener (perhaps) behave as if it were, does not vitiate economic reasoning to the extent that might be supposed. For these irrationalities (whether rational or irrational!) tend to offset each other. The applicability of the general “theory” of conduct to a particular individual in a particular case is likely to give results bordering on the grotesque, but en masse and in the long run it is not so. The market behaves as if men were wont to calculate with the utmost precision in making their choices. We live largely, of necessity, by rule and blindly; but the results approximate rationality fairly well on an average. (Knight, 1921: 67n1)

I don’t agree with everything Knight says here; I think he’s much too quick to assume that deviations from rationality will “offset”.13 But that’s something to be worked out on a case-by-case basis. We should not presuppose in advance either that the imperfections be irrelevant or that they will be decisive.

13 See Conlisk (1996) for many, many examples from both theory and practice where they do not.

Despite that, I quoted Knight here because there is an important point to I do agree with. If we don’t act by first drawing Marshallian curves and solving optimisation problems, how do we act? As Knight says, we typically act “by rule”. Our lives are governed, on day-by-day, minute-by-minute basis, by a series of rules we have internalised for how to act in various situations. The rules will typically have some kind of hierarchical structure - do this in this situation unless a particular exception arises, in which case do this other thing, unless of course a further exception arises, in which case, and so on. And the benefit of adopting rules with this structure is that they, typically, produce a good trade off between results and cognitive effort.

One useful role for idealised decision theory is in the testing and generation of these rules. We don’t expect people who have to make split-second decisions to calculate expected utilities. But we can expect them to learn some simple heuristics, and we can expect theorists to use ideal decision theory to test whether those heuristics are right, or whether some other simple heuristic would be better. This kind of approach is very useful in sports, where athletes have to make decisions very fast, and there is enough repetition for theorists to calculate expected utilities with some precision. But it can be used in other parts of life, and it is a useful role for idealised decision theory alongside its roles in prediction and explanation.

The other benefit of idealised decision theory is that it has turned out to be theoretically fruitful. This has included fruits that I, at least, would never have expected. It turns out that sometimes one gets a powerful kind of explanation from very carefully working out the ideal theory, and then relaxing one of the components of the idealisation. At a very high level of abstraction, that’s what happened with the Eyster and Rabin’s development of the notion of cursed equilibrium (Eyster & Rabin, 2005). The explanations they give for certain kinds of behavior in auctions are completely different from anything I’d have expected, but they seem to do empirically fairly well.14 Their models have people acting as if they have solved very complex equations, but have ignored simple facts, notably that other people may know more than they do. A priori, this is not very plausible. But if it fits the data, and it seems to, it is worth taking seriously. And while it was logically possible to develop a model like cursed equilibrium without first developing an ideal model and then relaxing it, that’s not in fact how it was developed. In fact the development of certain kinds of ideal models15 was theoretically fruitful in the understanding of very non-ideal behavior.

14 And there are even more empirically successful theories that build on their work, such as in Fong, Lin, & Palfrey (2023) and Cohen & Li (2023).

15 The ideal models they use, which involve the notion of Bayesian Perfect Equilibrium, are slightly more complicated than any model I’ll use in this book; they were not the simple models from the first day of decision theory class.

2.5 Summary

So our topic is idealised decision theory. In practice, that means the following things. The chooser can distinguish any two possibilities that are relevant to their decision, there is no unawareness in that sense, and they know when two propositions are necessarily equivalent. They can perform any calculation necessary to making their decision at zero cost. They have perfect recall. They don’t incur deliberation costs; in particular, thinking about the downsides of an option, or the upsides of an alternative, does not reduce the utility of ultimately taking that option, as it does for many humans. They know what options they can perform, and what options they can’t perform, and they know they’ll have that knowledge whatever choices they face. I’ll argue in Chapter 5 that it means they can play mixed strategies. Finally, I’ll assume it means they have numerical credences and utilities. I’m not sure this should be part of the same idealisation, but it simplifies the discussion, and it is arguable that non-numerical credences and utilities come from the same kind of unawareness that we’re assuming away. (Grant, Ani, & Quiggin, 2021)

So the problems our choosers face look like this. There are some possible states of the world, and possible choices. The chooser knows the value to them of each state-choice pair. (In Chapter 3 I’ll say more about this value.) The states are, and are known to be, causally independent of the choices. But the states might not be probabilistically independent of the choices. Instead, we’ll assume that the chooser has a (reasonable) value for Pr(s | c), where s is any one of the states, and c is any one of the choices. The question is what they will do, given all this information.